‘Kick Off! The start of spectator sports’ by Dr David Pendleton (Naked Eye Publications, 2018)

Cover of Kick Off by David Pendleton

Rear cover of Kick Off

I had been looking forward to the publication of this book and set aside an evening to digest. As it turned out my cup of tea was still warm by the time I’d finished reading. This is indeed a short book; it lacks illustrations and I doubt that there could be more than 40,000 words. Any shorter and it would probably be described as a pamphlet. The content of the book broadly mirrors that of the author’s 120,000 word dissertation about the origins of sport in Victorian Bradford minus its academic literature review. However there is the addition of references to womens sport, a number of which are lacking in substance but were presumably sufficient to meet the stipulations of the publisher.

The author examines a selection of the sporting activities undertaken in Victorian Bradford beginning with cricket and the early history of Bradford CC as well as entertainments such as knurr and spell, horse racing and pedestrianism that were common in the early to mid-century. The bulk of the coverage however relates to rugby and association football.

Bradford established for itself a reputation as a hotbed of sporting activity and enthusiasm in the nineteenth century, a pioneer of commercial rugby at Park Avenue and in the first decade of the twentieth century, of soccer at Valley Parade. Bradford witnessed a revolution in the commercialisation of sport and the transformation of sports clubs from recreational bodies to fully-fledged businesses. As in other northern towns, sport became an expression of civic patriotism and pride. Without a doubt Bradford offers a fascinating case study of how sport became commercialised and yet, until recently, what happened in Bradford has been given little attention and the early sporting history of the district had been forgotten.

Surprisingly there is very little coverage in the book to explain how the Bradford experience differed to what happened elsewhere in Great Britain or for that matter, elsewhere in the Anglophone world. Even a fleeting comparison of the experience in Bradford with that in say Newport, a similar industrial frontier town (and one likewise wedded to rugby) or with what happened in other industrial areas at the time would have been relevant. People seeking a broader perspective will be disappointed and the title is misleading by not making clear that it is concerned only with Bradford.

Described as a ‘popular edition’, being a distillation of his dissertation, I struggle to see what audience the author or the publisher is really trying to reach. ‘Kick Off! The start of spectator sports’ does not bring fresh observations or frameworks to the wider academic discussion about nineteenth century sport which may explain why the original dissertation has not been published for an academic readership. It is equally challenging to see what it offers non-academic readers who will find it the equivalent of eating empty calories. On this occasion neither is there any outstanding graphic design to compensate. All told it seems more like a vanity publication for its own sake.

Ultimately my criticism of this book is derived from the omission of a number of key themes from the author’s discussion of spectator sports becoming established in Bradford. Given that they would explain how and why commercialised sport developed as it did in Bradford – with distinct, local characteristics – it is not insignificant that they should have been missed out.

I am credited in the foreword with having provided the author with assistance (although I did notice that my books are not listed at the back of his own for further reading or reference). However the credit should not be interpreted as an implied endorsement of what he has written because quite clearly he has not read what is in my own books or articles published online (VINCIT etc – links below).

I am genuinely surprised that during the course of his doctoral research Pendleton failed to identify the motive of charity fundraising; the role of the Rifle Volunteers (territorial army); the influence of cricket on the commercial development of football; of how Bradford CC had been conceived in 1836 as an electoral vehicle by the Tories; the importance of the railways; the impact of urban geography and the property market; or the pioneering efforts of Jack Nunn – all of which were critical in the origins of sport and the eventual development of professional sport across the town. Mention is also lacking of how Bradford FC became known as a team of celebrities, the club that provided more England internationals before 1895 than any other in the north of England. Each of these is a major omission and collectively it undermines his credibility. For the author to have missed so much raises fundamental doubts about his scholarship.

Incredibly none of these examples afforded a mention in his dissertation – let alone in this book – and hence it is difficult to avoid the charge that Pendleton’s coverage is both superficial and patchy.

There is not even a footnote reference about the Bradford Charity Cup launched in 1884 which had a massive role in the development of a local football culture. Its influence was not just confined to rugby and can be linked to subsequent local rivalries in the Bradford & District Football League (from 1899) and the Bradford Cricket League (after 1903), as well as being a formative influence on Bradford cricket’s Priestley Cup.

Whilst there is considerable discussion of how public houses promoted leisure attractions and sporting entertainments as commercial initiatives in the mid nineteenth century, no mention is given of how the town fathers sanctioned a cultural commitment to recreation in Bradford through the development of civic parks across the district. The town’s first had been Peel Park which opened in 1853, becoming the venue for the popular West Riding galas and military tattoos that were the original mass spectator events in Bradford.

Although a distinct development, Park Avenue (opened in 1880) should be seen in the context of the programme of new public parks that followed in the decade after the opening of Lister Park in 1873 (ie Horton Park (1878), Bowling Park (1880) and Bradford Moor Park (1884)). Those parks were a source of considerable municipal pride and a statement that Bradford, and Bradford people, valued recreation. Park Avenue thus shared the cultural spirit that those parks represented. Crucially Bradford sports clubs saw themselves following in the tradition of respectable recreation as distinct from public house and showground ventures such as those at Quarry Gap, Dick Lane that were considered vulgar and mercenary, a point missed by Pendleton.

Likewise the author fails to explain how ‘football’ (in the case of Bradford, rugby) achieved such a broad take-up during the second half of the 1870s through to the triumph of Bradford FC in the Yorkshire Cup in 1884. A major factor in this was the extent to which social groups in Bradford were networked, linking people as diverse as those associated with half-day closing campaign groups, Volunteers, merchants, warehousemen and Scottish immigrants. No recognition is given to the importance of the Leuchters Restaurant in Kirkgate, Bradford as an important early meeting place for sports enthusiasts. Social networks were a vital mechanism to build popular support for the game in Bradford, another subtlety that has been missed.

One of the biggest influences on the commercial development of rugby in Bradford in the final quarter of the nineteenth century was the railways. The urban geography of the town and its topography created limitations on where the game could be played and the catchment of potential spectators. The railways played a major role in making venues accessible to people living within and without the district. The best illustration of this was the site adjacent the Stansfield Arms at Apperley Bridge and it was no coincidence that each of the major grounds in Bradford were within walking distance of a railway connection: for example not just Valley Parade and Park Avenue but Usher Street (St Dunstans station) and Bowling Old Lane (Bowling). During the 1870s, rugby fixtures at Peel Park and Lister Park similarly benefited from the proximity of Manningham station. Railways also allowed Bradford FC to establish a national reputation through tours to Scotland and the south of England and railways were the means by which teams could visit the town and allow Bradford people to attend games elsewhere in the county.

Equally surprising is that his discussion of gate-taking football clubs is confined to Bradford FC and Manningham FC (not Bradford RFC and Manningham RFC as he refers) which overlooks the significant number of junior clubs in the Bradford district who operated as commercial undertakings – the likes of Shipley FC, Bowling FC, Bowling Old Lane FC and other village sides. The story of how they failed is equally relevant to understand why others were successful.

Nor is there any reference to other participation sports such as athletics, cross country running, swimming, gymnastics, cycling, lacrosse, rowing, skating or even chess. Recognition of the fact that a number of these spawned commercial activity would have been relevant, as would comment about why they failed to become established as spectator sports even though on occasions large crowds assembled in Bradford to watch competitors in some of these activities.

There is also a number of historical inaccuracies in the book, for example the statement that the first attempt to launch an association club in Bradford was in 1895 and the suggestion that former Park Avenue chairman Harry Briggs was known for having been a former player. The first recorded instance of women’s football was not in Inverness in 1888 but Edinburgh in 1881 and in that earlier year there was even a match at Windhill, Shipley. Nor was it the case that Manningham FC was actively involved in raising funds on behalf of strikers during the Manningham Mills dispute in 1891. Amusingly Pendleton refers to the fact that Manningham RFC (sic) have oft been described as ‘a peoples’ team’. Amusing because to my knowledge it is only he who has ever done so, a description that is of dubious validity as I have said before.

With regards female participation in football, the author overlooks the practice of games being staged for the amusement and titillation of spectators, principally as shows of farce and mockery. For example, newspaper accounts of games at Windhill in 1881, Valley Parade in 1895 and Park Avenue in 1917 are consistent in highlighting that those attending had not done so for the purpose of watching football. Neither is there mention of the practice of mixed pantomime matches which were staged at Valley Parade and Park Avenue after 1891 involving entertainers from the Bradford theatres. These were initially rugby games but later, soccer and despite being staged for charity, the FA adopted a rather highbrow attitude in 1907 declaring that they did not want the game to become pure burlesque. (Quite likely the same attitude was one of the factors in the FA ban on female football introduced in 1921.)

‘Kick Off!’ provides a broad outline of what happened in Bradford in the nineteenth century but singularly fails to provide explanation of the how and why. It’s not simply that the author has overlooked a number of key points which is a major failing in itself. It is the lack of a bigger picture perspective that has denied him the means to identify the same underlying themes impacting on successive decades – the themes which shaped the development of sport in the city with distinctly local characteristics. In so doing, Pendleton has not grasped his opportunity to be original which should have been possible even within the word limit.

Submission of a doctoral dissertation requires a review of what others have already written on the candidate’s chosen subject. Having read his original dissertation I can see that Pendleton fulfilled this in great detail but I can’t help feeling that he spent more time thinking about what other people had written about other places than developing his own thoughts about somewhere (ie Bradford) that had previously been overlooked by academics. Hence he has missed many of the themes that were prominent locally quite simply because they may have been less relevant elsewhere and had not been flagged in the literature. Therefore, whilst his final dissertation was perfectly adequate to secure an academic qualification it’s not necessarily the basis for narrating a convincing account of what happened locally.

A further observation is that Pendleton’s reliance for the bulk of his research on the Bradford press denied him the more detached and candid observations provided by newspapers published in Leeds. Their reports would have afforded him an alternative and bigger picture perspective of events in Bradford and this shortcoming in his research is apparent in a number of the conclusions he reaches. Each of the Leeds papers, and the Yorkshire Evening Post in particular, had considerable coverage of Bradford sport. The celebrated YEP journalist, Alfred Pullin – known as ‘Old Ebor‘ (1860-1934) – was intimate with happenings in Bradford cricket and rugby, writing in detail about the town’s clubs and sportsmen yet he is not cited at all in Pendleton’s dissertation. Pullin it should be noted is recognised as having been a pioneer of sports journalism and an authority on late Victorian sport. He had himself played rugby in Bradford in his younger days.

Pendleton likes to presents himself as an authority yet is prone to leaps of imagination and narrating an imagined, wishful history. He can tell a good story but beware his casual sound bites that lack substance and defy critical examination. His claim for example that German money won the FA Cup for Bradford City AFC in 1911. There’s certainly no evidence for it in the club accounts of that era and no documented reference to such largesse in newspaper reports but heavens, don’t let it get in the way of him spinning a yarn. The same individual who claimed that Manningham FC was a bastion of ‘progressive politics’, ignorant of the inconvenient reality that the club leadership was dominated by Liberal Unionists and Tories.

The rear cover describes David Pendleton as ‘one of the north’s leading historians of sport and leisure‘. Seriously? If indeed that is the case – as opposed to being a casual statement of vanity – then the reader could reasonably expect more than sloppy research and assessment of findings that is neither thorough nor original. Either way it sets a standard by which this book can be judged. This book is certainly not a good advert for his supposed skills of scholarship.

‘Kick Off!’ reads better as individual chapters or essays in isolation rather than as a complete publication and it is a bit like the curate’s egg with some parts better than others. The book lacks a thread providing linkage between the constituent parts and reads like a compilation of disparate stories about a limited selection of Bradford sport that the author has struggled to meld into a whole. The reader is left with more questions than answers and without satisfactory explanations for how – and why – the development of sport in Bradford came to be shaped as it did. Even at £8.99 (*) I am not convinced that it is worth the money and besides, it makes a mockery of Dr Pendleton’s supposed stature in the academic world. The publisher boasts that this is a readable and accessible book which is indeed the case. It’s just a shame about the content and the empty calories.

(*) As at September, 2021 reduced in price to £2.15 on Amazon but still not worth the price or indeed the postage.

John Dewhirst

I have written widely about the history of sport in Bradford and you will find various features on this blog.

My two most recent books, ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP narrate the origins of sport in Bradford and its subsequent development. Further details can be found at: BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED BOOKS

The following is a summary link of online Articles by John Dewhirst on the history of Bradford sport

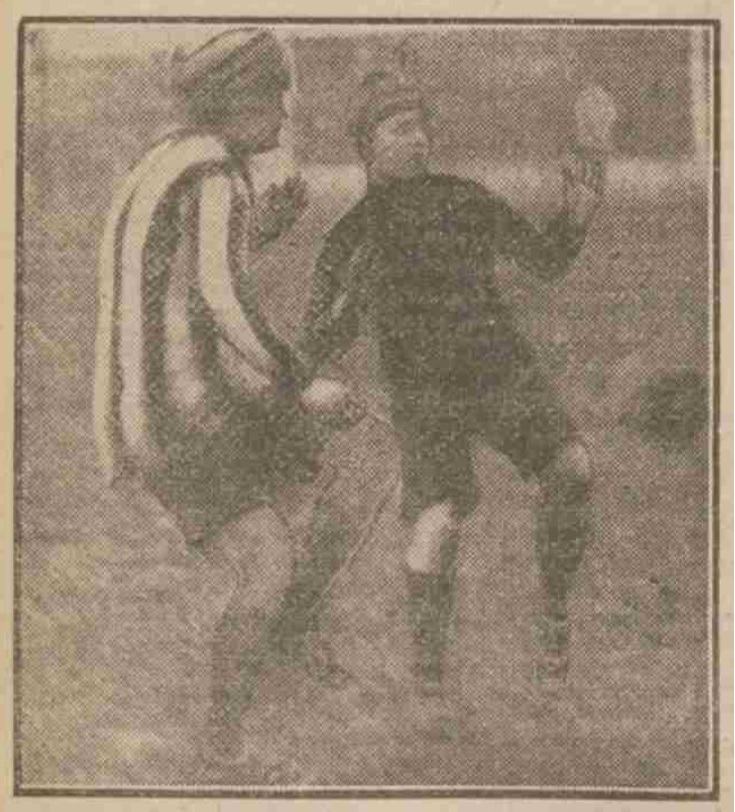

Thank you to David Wilkins for sending a photo of that game which shows DKL in stripes.

Thank you to David Wilkins for sending a photo of that game which shows DKL in stripes.