‘How Football Began: A Global History of How the World’s Football Codes Were Born’ by Tony Collins (Routledge, 2018), softback £19.99

Tony Collins is a prolific author having originally established his reputation recording the history of Rugby League and then Rugby Union, followed by narrating the global spread of rugby. His latest book investigates the origins of football in the nineteenth century and how different codes evolved through the Anglophone world to become a global phenomenon, all the more remarkable for the fact that each of the principal codes emerged within the space of a generation in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

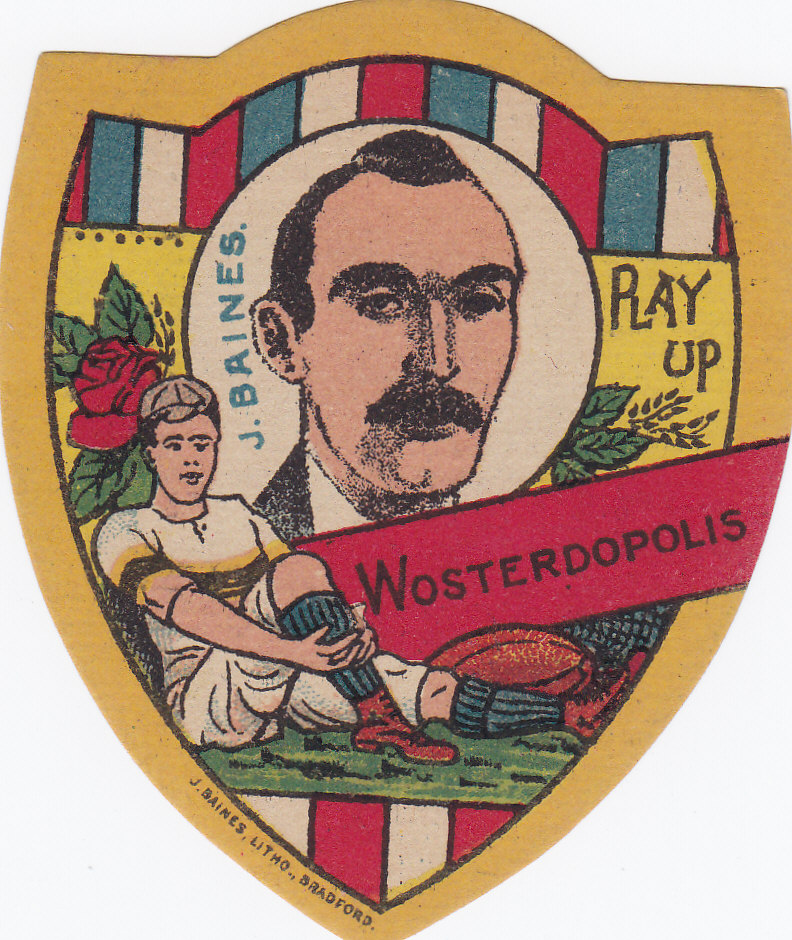

Sports histories have traditionally focused on single codes and historians have tended to overlook the parallels and similarities in different sports. In Bradford for instance, those interested in the history of the city’s association football clubs have tended to neglect the history of rugby football. Rugby League supporters have been equally dismissive of Rugby Union. It is all the more surprising given that in Bradford the two senior football clubs changed codes not once, but twice from Rugby Union to and then from the Northern Union to become ‘soccer’ clubs.

Collins highlights the fact that for the Victorians, football was a single game played under different rules. Newspapers and the public alike referred to football whether played with an oval or round ball and in West Yorkshire, rugby was commonly known as football (and football as soccer) prior to World War One. It is a crucial but fundamental observation that encourages new perspectives about the origins of soccer and rugby, encouraging a different interpretation of how football in the widest sense became commercialised to become an industry in itself. At a stroke Collins also shatters the longstanding myth that Sheffield FC (established in 1857) should be credited as pioneers of association football by pointing out that the club regularly played games according to rugby rules until as late as 1876. Similarly Collins highlights the influence of cricket clubs and cricket culture upon the formation of footballing sides – a good example of which is Bradford FC whose formation in 1863 was linked to Bradford Cricket Club on whose ground ‘football’ was first played. Indeed I can attest that in Bradford, cricket provided the DNA for organised sport.

In fact Collins could have added that the Victorians originally regarded football as merely another branch of athleticism and that during the 1860s there were other activities – among them gymnastics, assaults at arms, athletics, rowing, swimming and from 1868, cycling – that young men began to dabble with. Again in Bradford there is evidence that each of these, as well as football, became subject to the whims of fashion among those who had the time or money to indulge. The conclusion I have derived was that around this time there was considerable enthusiasm to experiment and in Bradford, cricket was considered distinctly passe. Notable also was the fact that membership of the Rifle Volunteers had also become popular after the launch of the movement in 1859 and not only did this encourage a passion for soldiering but athleticism as well. The example of Bradford clearly demonstrates that people were receptive to sporting activity and that a form of pent-up demand helped drive the explosive growth of football.

There is a strong case to be made that any history of the origins of sport has to be written bottom-up, based around an understanding of what happened in individual towns. Collins does this admirably with chapters in respect of Sheffield, Glasgow as well as Melbourne. Inevitably I am inclined to compare my knowledge of the experience in Bradford with what happened elsewhere. Broadly speaking it accords to the narrative at a national level although there were notable local characteristics that defined the course of events. As I have written in Room at the Top, it was the topography of Bradford and a shortage of flat areas suitable for playing sport that proved a critical factor and one that also ensured that soccer was crowded out for so long. Collins cites the church, the workplace and the pub as important drivers of the democratisation of football but gives no mention of the influence of the Rifle Volunteer movement and a notional commitment to charitable giving that proved significant in shaping Bradford sport. (NB In Bradford the influence of organised religion was limited.) Collins might also have mentioned that if Bradford is anything to go by, it was the influence of local personalities and so-called physical aesthetes – such as John Nunn – who were significant in promoting the cult of athleticism and with it making people open to new pastimes such as football.

Whilst Collins brings valuable insight into the origins of football, in my opinion there is another perspective that is lacking from his version of events. I might add that he betrays his RL heritage with his class-based narrative, in particular relating to the thorny issue of professionalism – the apparent raison d’etre of the Rugby League. In particular I am not entirely convinced by the suggestion that RFU opposition to professionalism was a form of ‘proxy for wider concerns about the rise of the working class’. What I consider to be missing is the perspective of an economic historian to explain how it was that sports clubs transformed themselves into businesses which in turn became members – and competitors – in an emergent industry. It was the conduct of the Bradford and Manningham football clubs as competing businesses which was the defining theme from my own findings into what happened in Bradford in the nineteenth century and it is this which offers an altogether different interpretation to the commercialisation of sport. The ascendancy of soccer over rugby by the end of the nineteenth century, like that of rugby over cricket a quarter of a century before can essentially be likened to the outcome of business cycles, the growth then maturity and decline curve of industries. That association football has succeeded in continually reinventing itself is another discussion but testament to the strong foundations and global reach established pre-World War One that Collins describes.

Given the explosive growth of football, one is tempted to look for a Big Bang moment of evolution, the stage at which creatures emerged from the oceans. Collins identifies cup competition as having been the catalyst – and in the case of Yorkshire football he cites the Yorkshire Challenge Cup (rugby) competition which began in 1877/78. But equally significant was how football clubs began monetising their activities and of how they persuaded people to pay to watch. This was the moment when football went from being dependent upon the supply of enthusiastic participants to the demand of potential spectators. For sure, cup competition set events in motion but it needed football clubs to have the necessary structures in place to become commercial entities. Adaptation to the new environment required business behaviours, the equivalent of former sea creatures now having to breathe oxygen. It was not simply footballers who facilitated the commercialisation of sport but administrators, club officials and emergent ruling bodies at a local level and this was not something that came out of nowhere. In this regard the example of Bradford shows how significant was the role of cricket in having already defined a commercial operating model that could be adopted and adapted by football.

Thus it seems incompatible for Collins to talk of sport being commercialised yet giving minimal reference to how sports clubs operated as commercial organisations. Besides, looking at football clubs as businesses offers alternative insights. The issue of professionalism for example can be seen as one concerned with wage control and profit management rather than necessarily about attempts to exclude working men from playing the game. An understanding of the profit motive likewise helps explain how clubs organised themselves and made decisions. Collins recognises that league structures came about for the purpose of optimising the profits of participant clubs but fails to acknowledge that in the north of England – and most certainly in Bradford – it was the economic implications of professionalism that carried more weight than any deep-rooted commitment to look after the interests of working men by paying them a wage. Furthermore, the leadership of the two senior Bradford clubs at Park Avenue and Valley Parade respectively were firmly Conservative (One Nation) in outlook.

My own study of Bradford confirms that the Northern Union’s emphasis on class identity (later inherited by the Rugby League) emerged only when that sport was facing the damaging impact of competition from professional soccer such that it sought to position itself as the authentic game of the people. Arguably this longstanding interpretation of RL history is contradicted by what happened in Bradford (and other northern towns) where working men continued to play Rugby Union and resisted the suggestion of throwing in their lot with the Northern Union until faced with the impending bankruptcy of their clubs. Junior sides in Bradford were unambiguous in their antipathy to the Northern Union after its formation in 1895 (which they regarded as a cartel established at their expense) and arguably had more in common with fellow Rugby Union sides based in leafy Surrey than the economic behemoth, Bradford FC on their doorstep at Park Avenue.

There is a temptation to view the Victorian sporting era as one of sportsmanship and pre-capitalist purity yet nothing could be further from the truth. Newspaper readers in the 1890s were equally aghast as their modern counterparts when informed about spiralling wage costs and football clubs veering perilously close to insolvency. Gambling was also endemic. And to suggest that this was a golden age of sportsmanship in England is wishful thinking. Returning again to class relations, there were good reasons why a team represented by sedentary middle class lawyers or businessmen should not relish the prospect of playing rugby against a team of manual labourers or miners.

Football was a dog eat dog world and the economic losers were equally as significant as the winners. Collins refers to the turnover of clubs and a high failure rate among early pioneers such that of the 32 clubs in the Football League in 1896 only eight had been formed before 1871 and of those only five were still in existence in 1901. A means by which clubs achieved economic advantage was through investment in grandstands and stadia that helped to redefine existing relationships and inequalities between them. This was evident first hand in Bradford after the development of Park Avenue in 1880 such that by the end of the decade the Bradford town club was reputedly one of the richest in Great Britain alongside Aston Villa. Yet by the end of the 1890s it would be overtaken by the wealth of those such as Everton and despite conversion to soccer in 1907, history records that the formerly pioneering Bradford FC remained very much a follower and overtaken by its former rugby rival Manningham FC who became Bradford City AFC in 1903.

My observations above do not detract from the opinion that How Football Began is a real tour de force and one deserving of wider readership beyond those with an academic interest. A strength of the publication is that it will encourage debate and the challenging of long established truths that have been taken for granted about the origins of football. The accompanying podcasts by Collins confirm that the punchy chapters are well suited to a radio or maybe even a TV series. Undoubtedly there is sufficient to capture public interest.

What distinguishes How Football Began is the sheer scope of its coverage and there are other dimensions that make it a unique publication. Collins’ style is very impressive, taking the reader across the continents with ease whilst also pausing to reflect on the fact that womens football never gained momentum. His chapter on womens football provides the sort of understanding that the vast majority of traditional football supporters (myself included) lack. To what extent the FA discriminated on the basis of misogyny as opposed to what it may have seen as a threat to the national game from the promotion of womens football as a spectacle for titillation and mockery is difficult to say. Either way it does not look good in the rear view mirror.

To be able to trace the parallel historical development of football in different continents is a considerable scholarly achievement. Again it is fascinating to make connections not just between the different codes but also geographies. Collins convincingly demonstrates the common origin as well as the similar growing pains of the different football codes in Australia, North America and Ireland (the common denominator of which was finance, again highlighting the need for this theme to be afforded prominence). He thus contradicts the efforts of the various codes to differentiate themselves as distinct and unique. In so doing I can’t help but think that How Football Began is capable of great mischief across the Atlantic. Whilst he credits the seminal influence of the British and the role of ex-pats who became sporting missionaries, he also highlights the influence of sporting culture in Melbourne, Australia and the manner in which Gaelic and Australian Rules football came to represent a nationalist identity as a counter to that of Imperial Britain. Football became a significant British cultural export not only across the Empire but in South America and Collins touches on how the game fascinated European visitors (in particular Germans) who launched their own clubs at home.

All told I warmly endorse this publication and can only encourage people to buy it. You can’t ask much more from a book that it should be original, engaging and thought provoking. As with all Tony’s other publications you get this in abundance and I look forward to the sequel.

John Dewhirst

I have written widely about the history of sport in Bradford and you will find various features on this blog.

My two most recent books, ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP narrate the origins of sport in Bradford and its subsequent development. Further details can be found at: BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED BOOKS

The following is a summary link of online Articles by John Dewhirst on the history of Bradford sport