It is nearly 50 years since Bradford Park Avenue AFC was voted out of the Football League at the end of the 1969/70 season. Nowadays it seems quaint to think that the city had two senior clubs and that the rivalry between City and Avenue should have been so emotional. With the liquidation of the original Park Avenue club in 1974, a sporting rivalry that stretched back 90 years to an era of rugby (both Rugby Union and Northern Union) was put to rest.

During the 1960s, if not the 1950s it had become increasingly likely that at least one of the two Bradford clubs would disappear as a consequence of financial failure. Until around 1967 it seemed that Bradford Park Avenue was more likely to survive. Miraculously, it was Bradford City under Stafford Heginbotham that achieved a revival whilst Avenue went into freefall. After finishing second to bottom of the basement division in 1966/67, the following three seasons they finished bottom. The meltdown was spectacular and Bradford Park Avenue – or rather, Bradford – finished far adrift from their nearest rivals in the bottom four places.

The embarrassment was made all the worse by the unwelcome headlines drawing attention to the dysfunctional off-field affairs at Park Avenue. If ever there was a case study of a football club imploding, this is it. Jeremy Charnock’s book Diary of a Lost Cause: Bradford (Park Avenue) AFC – 1966-1970 was published last month and is a detailed chronicle of Bradford’s last four seasons in the Football League, a weekly record of a football club’s sorry and pitiful collapse.

The author was familiar with the period as an Avenue supporter and had compiled a scrapbook of match reports from the Telegraph & Argus. The fact that it has taken him nearly fifty years to write his book probably says a lot about how painful was the experience of following his team. Indeed, you could be forgiven the observation that this publication has been a long overdue cathartic exercise for him.

Bradford (Park Avenue) crest 1971/72

Not that long ago I wondered if Bradford City might ‘do an Avenue’ and have a similar meltdown. What City supporters experienced during 2018 was not dissimilar to what happened at Park Avenue between 1966-70 as things fell apart both on and off the field. What we saw for ourselves was how easy it can be for the plates to stop spinning and an organisation become trapped in a downward spiral. In such circumstances it becomes increasingly difficulty to effect a turnaround and reverse the cycle of decline. The loss of confidence is debilitating, impacting everyone involved with a football club and a handicap to making a fresh start. So too a club becomes associated with failure and struggles to attract new talent or people who could make a difference to the way it is run.

Supporters become despondent and inevitably the gates decline. Before too long the problems are exacerbated by financial crises and decisions become increasingly short-termist. We saw for ourselves what happens when a club goes off the rails but thankfully the backwards drift at Valley Parade was arrested. Unfortunately, at Park Avenue things became progressively worse and by the end of 1969, if not much sooner it had become a hopeless situation.

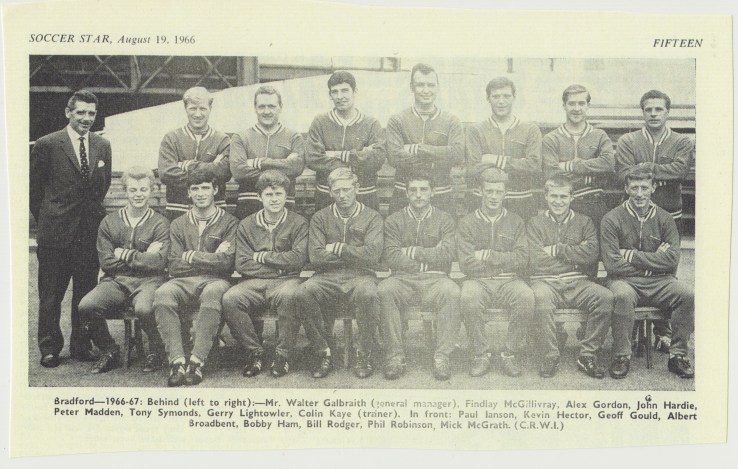

Jeremy Charnock rightly pinpoints the transfer of Avenue’s goal-scoring legend Kevin Hector to Derby County in September, 1966 as a crucial milestone. The failure to replace Hector was the headline failure of those in charge at Park Avenue although to be fair, it was always going to be a difficult task to replace someone of Hector’s class. Subsequent changes of manager had little impact and neither Jack Rowley nor Laurie Brown were capable of rebuilding the Avenue team despite funds (modest amounts but investment nevertheless) being made available by the directors. With boardroom squabbles thrown in, it seems that everything that could have gone wrong at Park Avenue did so. All that kept Bradford Park Avenue in the Football League for so long was the so-called ‘Old Pals Act’ and the re-election process to determine relegation from the competition.

What distinguishes this book is the extent to which team selection and decisions by managers as well as directors are diagnosed in meticulous detail. Those long ago seasons are relived on a weekly basis and it is fascinating to read about how people responded to disappointments and then tried to pick themselves up for the next game. It is a remarkably engrossing book and you sense that the author has long agonised over whether things could have turned out differently at Park Avenue. Indeed, Jeremy Charnock interviews a number of former players and club officials to ask exactly that and the responses are fascinating. Yet whilst the reader is left with the impression that the club did not have luck on its side in terms of how events turned out, the point that is missed is that the club’s existence was already precarious and finely balanced even before Hector was sold. Indeed, the underlying (and enduring) financial frailty of Bradford Park Avenue was the reason why Kevin Hector had had to be sold in the first place.

The micro analysis of Diary of a Lost Cause cannot be faulted but a detached (macro) perspective of Avenue’s circumstances as well as the club’s historical legacy is missing. The fact that Bradford City staged a recovery at the time that it was going pear shaped at Park Avenue undoubtedly added to the financial pressures as floating fans opted for Valley Parade in preference. The rivalry with City dictated football finances in Bradford and long before Avenue’s eventual demise it had been recognised that Bradford could not support two senior football clubs. In other words, with Bradford Park Avenue sitting on such shallow financial foundations it was always questionable how the club could ensure its viability.

The liquidation of Bradford Park Avenue in 1974 should be seen as the culmination of a lingering demise that went back much further than 1966. The acceleration in the decline of the club in its final four years in the Football League was the later stage of a process that had commenced much sooner. After the club’s relegation from the second division in 1950 the club had consistently struggled to stay afloat. Recurring financial difficulties had been a factor at Bradford Park Avenue ever since the death of the club’s original benefactor, Harry Briggs in 1920 and exacerbated following the resignation of the Waddiloves as bank guarantors in 1955. Therein was the cold reality that the club had always existed hand-to-mouth. In the absence of someone with deep pockets to fund its losses, Bradford Park Avenue could not defy financial gravity indefinitely.

In 1969 it seemed that Bradford had discovered a new benefactor and Herbert Metcalfe was the man who supporters hoped would transform the club’s finances. Metcalfe had had no prior football involvement and yet for reasons best known to himself wanted to become a director of a club at the bottom of the fourth division, rooted in 92nd position. Just about the only positive factor in its favour was that Bradford Park Avenue AFC owned its ground and other properties.

Jeremy Charnock is surprisingly charitable in relation to Metcalfe’s agenda whereas a cynic could be forgiven the suggestion that ulterior motives were at play. The most polite description would be to refer to him as a distress investor, the likes of whom have become more commonplace in English lower division football in the past fifty years. For good reason, supporters nowadays would be suspicious of a latterday Herbert Metcalfe but in 1969 it was a different environment and an unchartered phenomenon. It wasn’t that controversy didn’t exist, rather that people spoke in hushed tones and preferred to believe otherwise. However, subsequent disclosures arising from the Poulson scandal – and locally, the revelations of lax governance within Bradford Corporation – played their part in demonstrating to the public that the respectability of men in suits could not always be taken for granted. Inevitably it would encourage a degree of cynicism about people in positions of power in public institutions – football clubs included – that did not exist previously.

Modernity had seemingly fostered a more brazen approach on the part of those identifying investment opportunities in areas that had previously been off-limits, whether civic infrastructure or football clubs. In Bradford, the old cosy approach to doing things was being challenged and it was no coincidence that outsiders played their part in introducing new ways, from the influence of T. Dan Smith on the one hand to Herbert Metcalfe on the other. It was not necessarily without results – take for example the fact that the revival at Valley Parade had been spearheaded by another larger than life outsider, Stafford Heginbotham. So too the Park Avenue faithful had put their trust in a Lancastrian and accepted the need for radical change. (Equally telling is that a Bradford businessman had not come forth to bankroll either City or Avenue.)

By the time of Metcalfe’s appearance at Park Avenue, the affairs of the club were already so desperate that Avenue supporters were prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt. The apathy of Bradfordians about the city’s football clubs was another factor why the Metcalfe regime was given little scrutiny and so too the fact that it lasted little more than twelve months. However, that his involvement has not been investigated in detail is something of a glaring omission in Diary of a Lost Cause. This is particularly so given that Metcalfe’s behaviour had a big bearing on the perceptions of other clubs about how Bradford Park Avenue was being run – the same clubs whose goodwill and patience was vital to secure (and the ones who eventually voted to expel Avenue from the Football League at the end of 1969/70).

The fascinating question is how affairs might have been different had Herbert Metcalfe not died in October, 1970 although I am in no doubt that the die had been cast for Bradford Park Avenue long before. Whether Metcalfe would still have been acclaimed as a saviour of the club by its dwindling band of supporters seems unlikely. His death may have spared potential controversy and exposure.

Notwithstanding the judgement of Herbert Metcalfe, I recommend this book which provides an insightful record of players and managers struggling from one week to the next to lift their team. Pity Stanley Pearson, the T&A correspondent who must have struggled to write his match reports and balance the expectations of supporters, club officials and readers – as well as his professionalism – in what he wrote. And pity the fans who stood by their club. There but for the grace of God it could have been Bradford City in this situation.

Diary of a Lost Cause is a painful account about a dysfunctional football club and of how things went badly wrong. Whilst it concerns events that took place over fifty years ago, it is difficult to believe that the same basic ingredients of failure were unique to Bradford Park Avenue (even if the circumstances were exceptional) or for that matter, unique to the 1960s. As an antidote to the usual stories of football success and triumph, this is a book deserving a readership beyond former Avenue supporters still wrestling with what might have been. Diary of a Lost Cause is a publication that I heartily recommend.

=====================================

Diary of a Lost Cause: Bradford (Park Avenue) AFC – 1966-1970 by Jeremy Charnock (pub by 2QT, Dec-19) is available from the Bradford (PA) club shop, on ebay, Amazon and from the author: j.charnock@btinternet.com / 22 Rylands Avenue, Bingley BD16 3NJ RRP £25

=====================================

*** You can read my other book reviews from here.

The following is a link to a feature I wrote published on PLAYING PASTS in February, 2019 on The failure of football clubs.

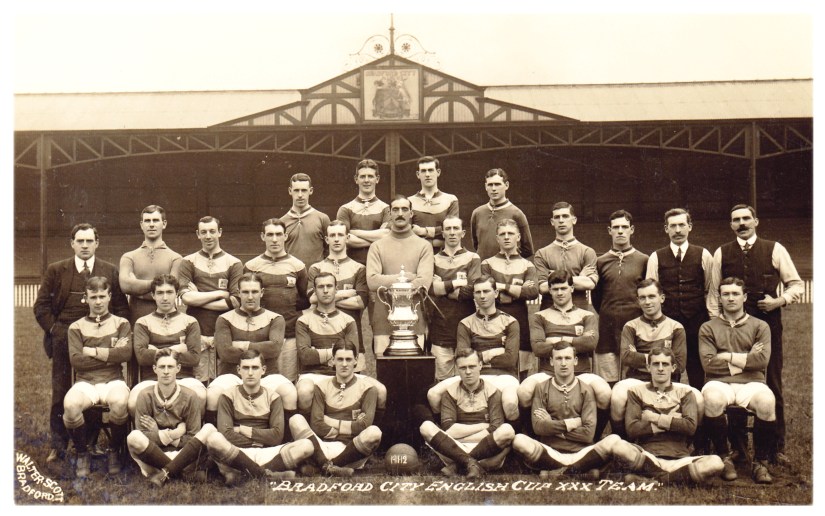

I am currently working on the history of the City / Avenue rivalry between 1908-74 that will be published in two, possibly three separate volumes. News of the first will be announced in early 2020 and will go on sale later in the year as part of the BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED series.